Henry Anatole Grunwald, long-time editor of TIME, once said, “Journalism can never be silent: That is its greatest virtue and its greatest fault. It must speak, and speak immediately, while the echoes of wonder, the claims of triumph and the signs of horror are still in the air.”

In today’s ever-connected world, people of all colors, stripes and backgrounds are now part of that journalistic struggle — they share stories, provide commentary and are just as part of the news as the sources, writers, and editors.

In the legacy model of the news, direct responses to news articles were shepherded to Letters to the Editor sections — a print version of today’s comment sections and forums. Newspapers and journalists liked this format, it gave them control of what to print, and allowed for civil discourse among reporters and readers — and even gave them new content to publish, for free.

However, lately we find media organizations and online newspapers throwing their hands up in frustration when it comes to the voices of their readers rather than use digital moderation tools to emulate the curating and posting of Letters to the Editor. Look no further than recent moves from Recode and Reuters ending user comments on news stories.

According to Reuters, “well-informed and articulate discussion around news, as well as criticism or praise for stories, has moved to social media.” If that’s true, then the time and attention of millions of people who consider the impact of world events has moved there too. And it’s hard to get these people back as media business trends tell us.

Research: Reader Participation on Social Networking Sites

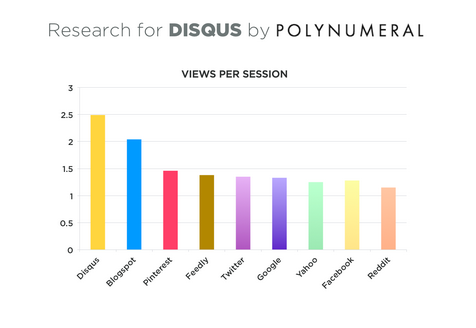

Research performed by a third-party data analysis firm Polynumeral shows that social media channels like Facebook and Twitter aren’t necessarily the right choice when it comes to reader participation. While we at Disqus commissioned this research, the findings are no less important.

What the research shows, is that readers who are referred to articles through Disqus are nearly twice as engaged than those who come from Facebook, Google, or Twitter. This means, readers who can comment on news articles directly where they are published, consume more content, stay longer, and are more likely to return. Don’t take our word for it. A Pew study from earlier this year said much the same.

A new arena for online discussions

By outsourcing these opinions to social channels, media organizations run the risk of creating shallower audiences, and therefore putting their existing sustainable business models based around readership monetization on shaky ground.

More ominous for a flailing industry model that has brought the death knell to many news organizations is what will happen if even more publishers give control over to Facebook for traffic and engagement. Two weeks ago, Digiday stated that “Facebook is reportedly pushing publishers — many of whom are already dependent on Facebook for a significant portion of their traffic — to start publishing stories within Facebook’s mobile app.” This alone should give organizations like Recode and Reuters pause.

Or as Mathew Ingram at Gigaom put it, if discussion “occurs somewhere else, then soon the readers who are interested in that engagement will start to think of the platform where it occurs as the important part of the relationship — not the site that actually created the content.”

While there will always be frustration and fury when debating the news, pushing the voices that shape the news off the digital page is not the answer. If anything, the only thing that is different today than when Henry Grunwald stated that journalism must “speak immediately, while the echoes of wonder, the claims of triumph and the signs of horror are still in the air” is that journalism must also include the voices of those it values — the readers.